What we'll talk about

In this article, we'll dive into the Tower of Hanoi puzzle from a developer perspective. We'll begin by exploring the origins and significance of this classic problem, followed by an analysis of the patterns and strategies involved in solving it. Finally, we'll walk through the implementation of an algorithm capable of solving the Tower of Hanoi for any number of disks, providing detailed explanations and code examples.

What you should know first

- Required: Fluency in at least 1 programming language

- Recommended: Basics of data structure and algorithms

Introduction

The Tower of Hanoi, also called "The problem of Benares Temple", "Tower of Brahma" or "Lucas' Tower", is a puzzle created by the french mathematician Édouard Lucas in 1883. This puzzle consists of 3 rods, with 1 rod initially holding a number of disks stacked in decreasing size, with the smallest disk on top.

The goal is to move the entire stack from one rod to another considering the following rules:

- Only one disk can be moved at a time.

- Each move consists of taking the top disk from one stack and placing it on top of another stack or an empty rod.

- No disk can be placed on top of a smaller disk.

According to legend, Brahmins at a temple in Benares have been moving the "Sacred Tower of Brahma," which consists of sixty-four golden disks, following the same rules as the Tower of Hanoi puzzle. It is said that completing this task will mark the end of the world

If the legend were true and the priests could move one disk per second, completing the puzzle with the minimum number of moves would take approximately 585 billion years — 42 times the estimated current age of the universe.

If you just met the puzzle, I recommend that you try the game using 2, 3 and 4 disks to get a feel for the challenge. You can play it here.

Why Tower of Hanoi

"Why should I bother learning how to solve a seemingly random puzzle?" you might ask.

Well, here are a few reasons:

Logical Reasoning

This is probably the most common reason why you should truly understand the Tower of Hanoi. Learning how it works will improve your capacity for logical reasoning and problem resolution.

Besides that, the algorithm that resolves the puzzle uses techniques that are essentials when it comes to how to resolve complex problems using code.

Mathematical Insight

The Tower of Hanoi is closely related to mathematical concepts such as geometric progression and exponential growth. Understanding the puzzle helps in grasping these concepts and their applications.

Historical and Theoretical Significance

The Tower of Hanoi has historical significance and is often discussed in theoretical computer science. Learning about it gives you a deeper appreciation of the field and its development.

Understanding the problem

The most effective approach to understanding how to solve the Tower of Hanoi for n disks is to start with fewer disks and observe the patterns. There's no need to attempt solving it with 5 or more disks initially, as the fundamental patterns can be grasped with 3 or 4 disks. Therefore, it's best to concentrate on these sizes first.

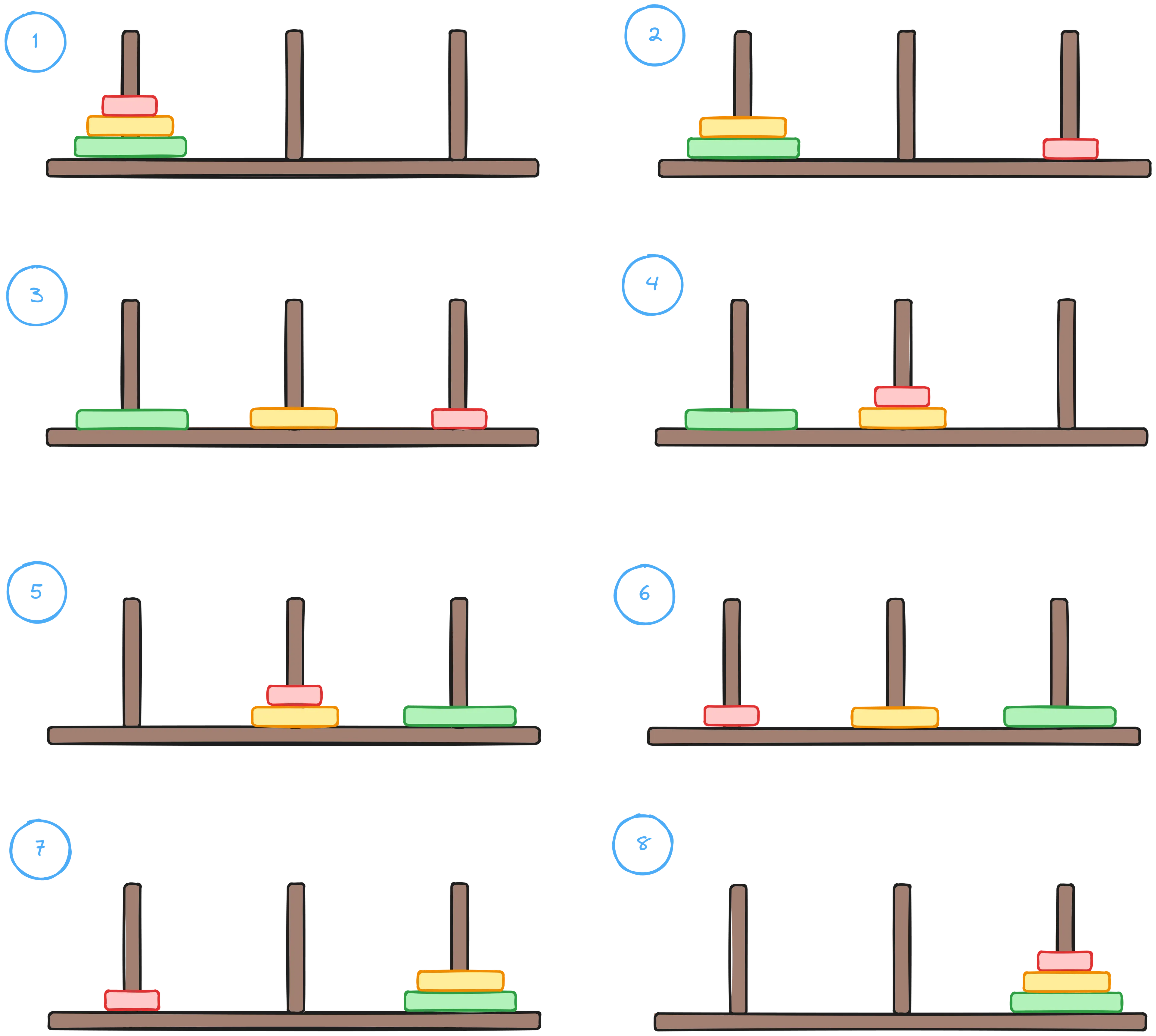

If you try to resolve the puzzle with 3 disks by your own you'll eventually end up in the following resolution:

Let's break down the resolution step by step:

- We start with three rods labeled A, B, and C from left to right. Rod A holds three disks labeled 1, 2, and 3, with 3 being the largest and 1 the smallest.

- The first thing that we want to do is move the disk 3 to rod C, but is not possible because it's blocked by the disk 2.

- So now the thing that we want to do is to move the disk 2 to rod B, given that we want to keep the rod C free to move the disk 3. Again is not possible because it's blocked by the disk 1.

- So now the thing that we want to do is to move the disk 3 to rod C, given that we want to keep the rod B free to move the disk 2. This time the move is valid so that's what we do (step 2 from image).

- Now the disk 2 is free to be moved to rod B, so that's what we do (step 3 from image).

- Now the disk 3 is free to be moved, but rod C has a smaller disk, so this move would not be valid. But we can move disk 1 to rod B since it has a larger disk, that way clearing the rod C (step 4 from image).

- Now the disk 3 is free to be moved to rod C, so that's what we do (step 5 from image).

- The disk 3 is now at the final rod, so we're not gonna move it anymore. The next step is to move the disk 2 to rod C, but it's not possible because it's blocked by the disk 1

- So now the thing that we want to do is to move the disk 1 to rod A, given that we want to keep the rod C free to move the disk 2. This time the move is valid so that's what we do (step 6 from image).

- The disk 2 is free to be moved to rod C, so that's what we do (step 7 from image).

- Finally, to complete the tower we want to move the disk 1 to rod C, the move is valid so that's what we'll do (step 8 from image).

- The Tower of Hanoi is done!

Before we continue I recommend taking a few minutes and observe the resolution above, try to identify patterns and write it down. This is useful to develop the skill of pattern discovering in the problems, turning them easier to resolve.

Done the investigation, here it comes the secret:

The core pattern of Tower of Hanoi revolves around breaking it down into smaller sub-towers. The whole resolution logic lives in understanding that resolving a 3 disks tower requires that you resolve a 2 disks tower, just like step 4 from the image resolution. This recursive nature continues: solving a tower with 3 disks entails solving a tower with 2 disks and then moving the 3rd disk, and solving a tower with 2 disks involves solving a tower with 1 disk and then moving the 2nd disk.

From this characteristic, we can infer that an algorithm solving the Tower of Hanoi naturally employs recursion.

A secondary characteristic, but also important, is noting that the target rod for each disk alternates. It means that if we want to move the disk 3 to rod C, than the disk 2 must be moved to rod B. And if we want to move the disk 2 to rod B, than the disk 1 must be moved to rod C.

Implementation

Our goal is to implement an algorithm that solves the puzzle using the fewest number of moves possible. To reach this, we'll use the language Go.

First, we need to model the elements of the problem in code. We'll start by implementing a Stack data structure and its common methods to represent each rod:

// stack.go package main type Stack struct { data []int } func (s *Stack) Push(value int) { s.data = append(s.data, value) } func (s *Stack) Pop() int { index := len(s.data) - 1 element := s.data[index] s.data = s.data[:index] return element } func (s *Stack) Size() int { return len(s.data) } func NewStack() *Stack { return &Stack{ data: []int{}, } }

Stackis a struct that represents a rod- Each

Stackelement is a disk - The

Pushmethod adds an element at the top of the rod - The

Popmethod removes the element on top of the rod - The

Sizemethod returns the current size of the rod in number of elements - The

NewStackfunction creates a rod

Now that we have each rod representation, it's time to implement the structure that will represent the entire structure of towers:

// towers.go package main import "os" type TowerID string const ( A TowerID = "A" B TowerID = "B" C TowerID = "C" ) type Towers struct { A *Stack B *Stack C *Stack moves int } func (t *Towers) tower(towerID TowerID) *Stack { switch tower { case TowerID(A): return t.A case TowerID(B): return t.B case TowerID(C): return t.C } os.Exit(1) return nil } func (t *Towers) Move(fromID TowerID, toID TowerID) { from := t.tower(fromID) to := t.tower(toID) element := from.Pop() to.Push(element) t.moves = t.moves + 1 } func (t *Towers) Size(towerID TowerID) int { return t.tower(towerID).Size() } func (t *Towers) Moves() int { return t.moves; } func NewTowers(size int) *Towers { a := NewStack(size); for i := 0; i < size; i++ { a.Push(size - i); } return &Towers{ A: a, B: NewStack(), C: NewStack(), moves: 0, } }

TowerIDhas the role of an enum that represents ID's of each rod:A,BandC.Towersis a struct that represents the entire puzzle, containing the 3 rods and the total moves executed.- The

towermethod returns the correspondingStackfor a given rod ID. - The

Movemethod moves an element from one rod to another. - The

Sizemethod returns the number of disks on a specific rod. - The

Movesmethod returns the number of moves executed so far. - The

NewTowersmethod creates a newTowersinstance with a specified number of disks.

With these two structures we are almost ready to create the resolution algorithm, except for one detail. We already established that to resolve a Tower with 4 disks we first need to resolve a tower with 3 disks, so we need a way to scale the tower down and then scale it back up to the original size.

For this first we need to modify the Stack. For simplicity I'll only describe the methods that have been added or changed:

// stack.go type Stack struct { data []int limit int } func (s *Stack) Size() int { size := 0 for _, element := range s.data { if s.limit > element { size = size + 1 } } return size } func (s *Stack) Decrease() { s.limit = s.limit - 1 } func (s *Stack) Increase() { s.limit = s.limit + 1 } func NewStack(limit int) *Stack { return &Stack{ data: []int{}, limit: limit, } }

- We added the property

limitonStack. The purpose of this property is to filter the values in the stack, allowing us to manipulate the number of disks currently being used. - The

Sizemethod was modified to apply thelimitproperty as a filter, only counting elements smaller than the current limit. - The

Decreasemethod decreases current limit by 1. - The

Increasemethod increases current limit by 1. NewStackmethod now accepts alimitparameter to define the default limit.

Now we have to modify Towers in order to implement the limit logic:

func (t *Towers) Decrease() { t.A.Decrease() t.B.Decrease() t.C.Decrease() } func (t *Towers) Increase() { t.A.Increase() t.B.Increase() t.C.Increase() } func NewTowers(size int) *Towers { limit := size + 1 a := NewStack(limit) for i := 0; i < size; i++ { a.Push(size - i) } return &Towers{ A: a, B: NewStack(limit), C: NewStack(limit), moves: 0, } }

- The

Decreasemethod decreases the limit for allstacks. - The

Increasemethod increases the limit for allstacks. - The

NewTowersmethod has been updated to set the defaultlimitvalue for all stacks. The initiallimitis always equal tosize + 1, ensuring that the firstSizecall considers all disks.

Now it's time to implement the actually resolution:

// main.go package main import ( "fmt" "os" ) func NextTower(from TowerID, to TowerID) { ids := []TowerID{TowerID(A), TowerID(B), TowerID(C)} for _, s := range ids { if s == from || s == to { continue } return s } os.Exit(1) return TowerID(A) } func HanoiTower(towers *Towers, fromID TowerID, toID TowerID) { if towers.Size(fromID) == 1 { towers.Move(fromID, toID) return } towers.Decrease() HanoiTower( towers, fromID, NextTower(fromID, toID), ) towers.Increase() towers.Move(fromID, toID) towers.Decrease() HanoiTower( towers, NextTower(fromID, toID), toID, ) towers.Increase() } func main() { size := 3 towers := NewTowers(size) HanoiTower(towers, TowerID(A), TowerID(C)) fmt.Printf("Tower of Hanoi with %d disks takes %d moves to be completed", size, towers.Moves()) }

- The

mainfunction is the entry point of the algorithm. - The

NextTowerfunction implements the logic of alternating between rods. - The

HanoiTowerfunction is the one that actually resolves the puzzle

In the HanoiTower function we receive a Towers instance and the ID's of the origin and destination rods. By default, we aim to move all disks from rod A to rod C, but nothing stops us from move disks to or from rod B too.

As mentioned earlier, the Tower of Hanoi algorithm uses recursion, so the first step is to define the base case. In this algorithm the base case is a from rod with only 1 disk, given that we can simply move the disk to the destination.

Once there are more than 1 disk on the origin rod, we decrease its size by 1 and recursively call the HanoiTower method again, but with the reduced size and changing the destination rod according to the alternating pattern.

This recursive process continues until the origin rod contains only 1 disk, our base case.

Once it hits the base case the algorithm will start to bubble up. We increase the tower back by 1 and actually move the disk from rod specified in parameters to the rod also specified in parameters.

Than we decrease back the tower and recursively call HanoiTower function again. This time, we move the disks that were alternated to the final destination rod specified in the parameters.

Let's break down an example using a tower with 3 disks:

-

- The algorithm begins with a tower of 3 disks on rod

A, aiming to move them all to rodC.

- The algorithm begins with a tower of 3 disks on rod

- The first execution does not fit into the base case, since from rod has 3 disks size. So we call the

HanoiTowerfunction recursively decreasing the tower by 1 and changing the destination toB. - The second execution also does not fit the base case, since the from rod has 2 disks size (the disk

3is being ignored because of tower decrease). So we call theHanoiTowerfunction recursively decreasing again the tower by 1 and changing the destination back toC. - The third execution now fits the base case, since the from rod now has only 1 disk size because of the two previous decreases. In the base case we just move the target to destination, so now the disk

1is at rodC. - The algorithm will now start to bubble up, so we're back in second execution. After the recursive call to

HanoiTowerwe just move the target disk to destination. So the disk2is now at rodB. - Then we call

HanoiTowerrecursively again, but now the goal is to move the alternated disk1to the rodB, thus completing a 2 disks size tower. This recursive call also hits the base case since rodCnow has only 1 disk. - The execution bubbles up again and now we are back at the first execution. After the recursive call to

HanoiTowerwe just move the target disk to destination. So the disk3is now at rodC. - Then we call

HanoiTowerrecursively again, but now the goal is to move the alternated disk2(that is at rodB) to the final destination rodC. - Since the rod

Bnow has 2 disks size, we decrease the tower and callHanoiTowerrecursively with destiny to towerA, following the alternating rule. - Now the execution will hit the base case. Since the tower was decreased, the rod

Bonly has 1 disk size. So the disk1is now at rodA. - The algorithm bubbles back to the second execution, so we move the disk

2to rodC. - Then we call

HanoiTowerrecursively to move disk1to the final destinationC. - Tower of Hanoi with 3 disks completed successfully!

The algorithm probably may seem complicated at first, but I recommend that you read the step-by-step explanation a few times to grasp the concept. After that, I encourage you to implement the algorithm in your favorite programming language on your own. This hands-on approach will solidify your understanding.

Big O

Now we're going to analyze the asymptotic complexity of the Tower of Hanoi algorithm that we implemented using Big O notation. For didactic purposes we'll only consider the number of disks moves instead of consider the complexity of every single helper method.

At first sight, it will probably be difficult to discover the complexity, so let's write down the number of moves executed for each size of the tower:

| Size | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moves | 3 | 7 | 15 | 31 | 63 | 127 | 255 |

Well, to be honest the table does not really help us to discover the algorithm complexity. It's hard to find a pattern in those numbers if you never seen that kind of steps growing before.

In this case we'll need to use other resource to help us: math. You can read more about it in the article "Tower of Hanoi from a Math Point of View".

References

- Book Concrete Mathematics, Second Edition, by Ronald L. Graham, Donald E. Knuth, and Oren Patashnik